Science & Technology

/Knowledge

Sharks 'adapting their movements and routines,' great white researchers discover

Do great white sharks change their behaviors in different environments, or do the apex predators follow the same routines regardless of location?

Researchers recently set out to solve this shark puzzle, as they reportedly discovered great white behaviors by attaching smart tags and cameras to their fins.

Great whites adapt their movements and ...Read more

Health care is a tough arena for AI to make a difference

It was a warp-speed tour of what's happening with artificial intelligence in medicine.

Chris Manrodt, an R&D manager for Philips' medical imaging business in Plymouth, Minnesota, last Friday gave a presentation to several hundred Twin Cities software developers and health care executives and then declared, "I feel like I've said about 50 ...Read more

How trains linked rival port cities along the US East Coast into a cultural and economic megalopolis

The Northeast corridor is America’s busiest rail line. Each day, its trains deliver 800,000 passengers to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington and points in between.

The Northeast corridor is also a name for the place those trains serve: the coastal plain stretching from Virginia to Massachusetts, where over 17% of the country...Read more

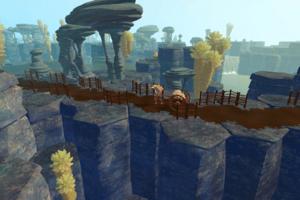

‘Dune: Awakening’ takes fans to Arrakis and forces them to survive a wasteland

“Dune” may not seem like a natural setting for a survival MMO. Players explore the desert planet of Arrakis and resources appear scarce, but the developers at Funcom are huge fans of Frank Herbert’s work and heavily influenced by director Denis Villeneuve’s films. They know there’s more under the surface, and the team led by creative...Read more

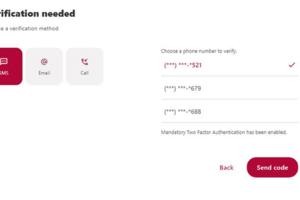

Jim Rossman: Helping mom secure her online banking

I spent a recent weekend visiting with my mom, and she had a rather short list of technical things she needed my help with on this trip.

The first was easy – she has a new Wyze doorbell and it had lost its connection to her Amazon Echo.

When I set it up, her Echo Dot would announce when someone was ringing her doorbell. The Echo would also...Read more

Gadgets: Make your phone truly hands-free

Ohsnap's Snap 4 Luxe is a multifunctional accessory that truly makes smartphones hands-free. It attaches to the back of a phone and is ready to stick to any metal surface around your house or office. With the accompanying Snapmount 2.0 wall mount, it can be put anywhere.

While Apple MagSafe comes to mind, it is not limited to just that ...Read more

‘Bitcraft: Age of Automata’ wants players to rebuild civilization from the ground up

The developers behind “Bitcraft: Age of Automata” want you to build the world from the ground up. Villages, towns, cities, nations and empires are all in players hands. That’s how Clockwork Labs envisions for its ambitious sandbox massively multiplayer online game.

Players start with primitive tools. Like other survival games, they’ll...Read more

Illinois residents encouraged to destroy the eggs of invasive insects to slow spread

CHICAGO — While Chicagoans were alarmed to learn the spotted lanternfly had been found in Illinois last year, experts say spring is the time to take action against that insect — as well as another damaging invasive species that has made far more inroads and gotten less attention.

The spongy moth, formerly known as the gypsy moth, has been ...Read more

Steelhead trout, once thriving in Southern California, are declared endangered

Southern California’s rivers and creeks once teemed with large, silvery fish that arrived from the ocean and swam upstream to spawn. But today, these fish are seldom seen.

Southern California steelhead trout have been pushed to the brink of extinction as their river habitats have been altered by development and fragmented by barriers and dams...Read more

Climate change supercharged a heat dome, intensifying 2021 fire season, study finds

As a massive heat dome lingered over the Pacific Northwest three years ago, swaths of North America simmered— and then burned. Wildfires charred more than 18.5 million acres across the continent, with the most land burned in Canada and California.

A new study has revealed the extent to which human-caused climate change intensified the ...Read more

Plan to kill Catalina Island deer using sharpshooters in copters is opposed by LA County

LOS ANGELES — A plan to kill all the mule deer on Catalina Island using aerial sharpshooters from helicopters was strongly opposed by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday.

The controversial program as proposed by the Catalina Island Conservancy aims to eradicate up to 2,000 deer on the island that the conservancy says are ...Read more

JFK Airport parking lot to become biggest solar array in New York

NEW YORK — The future is looking sunny for Kennedy Airport’s long-term parking lot No. 9.

Construction began Tuesday on a solar array meant to cover some 21 acres of the lot while maintaining the car park beneath.

“If that sounds big, it is,” said Rick Cotton, executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

“It ...Read more

Reintroduced gray wolf found dead in Larimer County, Colorado

DENVER — One of 10 gray wolves reintroduced to Colorado in December was found dead in Larimer County, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service confirmed.

Federal officials found out about the wolf on Thursday, agency spokesperson Joe Szuszwalak said in an email Tuesday night.

Initial evidence shows the wolf likely died of natural causes, ...Read more

SpaceX launch marks 300th successful booster landing

ORLANDO, Fla. — SpaceX sent up the 30th launch from the Space Coast for the year on Tuesday evening, a mission that also featured the company’s 300th successful booster recovery.

A Falcon 9 rocket carrying 23 of SpaceX’s Starlink internet satellites blasted off at 6:17 p.m. Eastern time from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space ...Read more

What is curtailment? An electricity market expert explains why states sometimes have too much wind or solar power

Curtailment has a special meaning in electric power systems. It describes any action that reduces the amount of electricity generated to maintain the balance between supply and demand – which is critical for avoiding blackouts.

Recently, curtailment has made news in states like California and Texas that are adding a lot of wind and ...Read more

Superfund designation for PFAS raises concern over liability

WASHINGTON — The EPA has issued a final rule that will list the two most widely used forms of PFAS chemicals under the law governing Superfund sites, spurring worries in Congress over the liability for industries that merely received products that contained them.

The agency’s final rule designates perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, and ...Read more

SpaceX launch this evening would mark 300th booster landing if successful

ORLANDO, Fla. — SpaceX is set to send up the 30th launch on the Space Coast this year targeting an evening liftoff Tuesday that would see the 300th booster recovery if successful.

A Falcon 9 rocket carrying 23 of SpaceX’s Starlink internet satellites is aiming to launch at 6:17 p.m. at the opening of a four-hour window Tuesday that runs ...Read more

State's new law involving PSE aspires to set a course for the future

SEATTLE —Over the past couple of years, Washington lawmakers have wrestled with a daunting task.

The problem: The state's largest utility, Puget Sound Energy, sells natural gas to nearly 1 million customers and burns gas and coal to electrify cities. That contributes millions of metric tons of planet-warming gases to the atmosphere.

It makes...Read more

Wildlife agency: Sturgeon won't go on endangered species list

Fishing for lake sturgeon in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan is not a threat to the ancient species, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded in its decision not to list the giant fish under the Endangered Species Act.

Monday's ruling after a yearlong review ends the possibility the largest freshwater fish in North America will be put off...Read more

ENV-STURGEON // Wildlife agency: Sturgeon won't go on endangered species list

Fishing for lake sturgeon in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan is not a threat to the ancient species, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded in its decision not to list the giant fish under the Endangered Species Act.

Monday's ruling after a yearlong review ends the possibility the largest freshwater fish in North America will be put off...Read more

Popular Stories

- ‘Dune: Awakening’ takes fans to Arrakis and forces them to survive a wasteland

- How trains linked rival port cities along the US East Coast into a cultural and economic megalopolis

- Gadgets: Make your phone truly hands-free

- Jim Rossman: Helping mom secure her online banking

- ‘Bitcraft: Age of Automata’ wants players to rebuild civilization from the ground up