Science & Technology

/Knowledge

Wild turkey numbers are falling in some parts of the US – the main reason may be habitat loss

Birdsong is a welcome sign of spring, but robins and cardinals aren’t the only birds showing off for breeding season. In many parts of North America, you’re likely to encounter male wild turkeys, puffed up like beach balls and with their tails fanned out, aggressively strutting through woods and parks or stopping traffic on your street....Read more

Reintroduced wolves kill 4 yearling cattle in latest of string of livestock attacks in Colorado

DENVER — Wolves killed several yearling cattle in north-central Colorado this week, bringing the total number of wolf kills of livestock this month to six.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife on Thursday confirmed that wolves killed three yearlings on a Grand County ranch between Monday night and Tuesday morning. The carcasses were discovered ...Read more

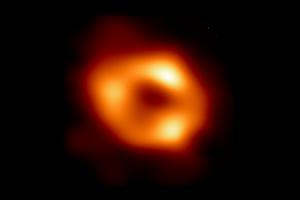

Groundbreaking discovery: Astronomers find largest black hole in Milky Way

Astronomers have discovered the largest known stellar black hole in the Milky Way, according to a European Space Agency news release.

Named Gaia BH3, it was found by chance when the space agency’s Gaia mission team was combing through data. With a mass 33 times that of the sun, BH3 surpasses the previous record holder, Cyg X-1, which is about...Read more

Planned 'mass execution' of geese in Conn. city paused after outpouring of passionate input on both sides

HARTFORD, Conn. — Tears, shouts and interruptions marked residents’ comments Wednesday night over a proposal to exterminate geese in Bristol, Conn., parks.

As the city’s Board of Parks considered a proposal to kill resident geese that are causing excessive waste that is marring Veterans Memorial Park, dozens of residents shared ...Read more

Billions of cicadas are about to emerge from underground in a rare double-brood convergence

In the wake of North America’s recent solar eclipse, another historic natural event is on the horizon. From late April through June 2024, the largest brood of 13-year cicadas, known as Brood XIX, will co-emerge with a midwestern brood of 17-year cicadas, Brood XIII.

This event will affect 17 states, from Maryland west to Iowa and ...Read more

Fewer loon chicks surviving because of climate change, researchers say

For three decades, David Johnson has guided nature lovers in early spring to northern Illinois lakes to hear the eerie yodeling of hundreds of common loons.

Within the next 30 years, however, there may be few if any migrating loons in Illinois, according to Walter Piper, researcher and professor of biology at Chapman University in Orange, ...Read more

Sealing homes' leaky HVAC systems is a sneaky good climate solution

There's a hidden scourge making homes more harmful to the climate and less comfortable: leaky heating and cooling systems. Plugging those leaks may be the dull stepchild of the energy transition, but that doesn't make it any less important than installing dazzling solar arrays and getting millions of electric vehicles on the road.

The problem,...Read more

LA's water supplies are in good shape. But is the city ready for the next drought?

LOS ANGELES -- California’s second wet winter in a row has left L.A’s water supplies in good shape for at least another year, but the inevitable return to dry conditions could once again put the city’s residents in a precarious position.

After the state’s final snow survey of the season, officials with the Los Angeles Department of ...Read more

Editorial: If 10 straight months of record-breaking heat isn't a climate emergency, what is?

Californians have had weekend after weekend of cool, stormy weather and the Sierra Nevada has been blessed with a healthy snowpack. But the reality is that even the last few months have been more than 2 degrees hotter than average.

The planet is experiencing a horrifying streak of record-breaking heat, with March marking the 10th month in a row...Read more

NASA Langley is testing solar sail technology that could reduce costs of space missions

A sunlight-propelled satellite floating though space on huge metallic sails sounds like an idea straight from science fiction.

But scientists at NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton have spent five years making the technology a reality and plan to launch a test mission as soon as April 23. If successful, the sail technology could reduce the ...Read more

SpaceX tallies 1st of 2 launches over 2 days from Space Coast

ORLANDO, Fla. — SpaceX launched Wednesday evening the first of a pair of Space Coast rockets in two days, both carrying batches of the company’s Starlink satellites.

A Falcon 9 rocket carrying 23 of the internet satellites for SpaceX’s growing constellation lifted off at 5:26 p.m. Eastern time from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Pad 39-A...Read more

White House renews internal talks on invoking climate emergency

WASHINGTON — White House officials have renewed discussions about potentially declaring a national climate emergency, an unprecedented step that could unlock federal powers to stifle oil development.

Top advisers to President Joe Biden have recently resumed talks about the merits of such a move, which could be used to curtail crude exports, ...Read more

Tech layoffs jolt Bay Area economy with hundreds of new job cuts

SUNNYVALE, California — A high-profile aerospace and defense contractor and a semiconductor company were among the latest tech firms to chop jobs in the Bay Area, cutbacks that will erase more than 200 positions.

Lockheed Martin, Coherent, and Hinge Health, a tech company that provides online physical therapy, have decided to slash employment...Read more

Canada to start taxing tech giants in 2024 despite US complaints

Canada will start applying a proposed tax on the world’s biggest technology companies this year, despite threats from American lawmakers to carry out trade reprisals against a levy that will primarily hit U.S. firms.

Legislation to enact the digital services tax is currently before Canada’s Parliament. Once it passes, “the tax would begin...Read more

Native American voices are finally factoring into energy projects – a hydropower ruling is a victory for environmental justice on tribal lands

The U.S. has a long record of extracting resources on Native lands and ignoring tribal opposition, but a decision by federal energy regulators to deny permits for seven proposed hydropower projects suggests that tide may be turning.

As the U.S. shifts from fossil fuels to clean energy, developers are looking for sites to generate ...Read more

Removing PFAS from public water will cost billions and take time – here are ways to filter out some harmful ‘forever chemicals’ at home

Chemists invented PFAS in the 1930s to make life easier: Nonstick pans, waterproof clothing, grease-resistant food packaging and stain-resistant carpet were all made possible by PFAS. But in recent years, the growing number of health risks found to be connected to these chemicals has become increasingly alarming.

PFAS – ...Read more

Jim Rossman: Fixing a non-working AirPod

Most of the time I write about issues other people are having, but today the problem I will tell you about happened to me.

I love to listen to sports talk radio at lunch if I’m eating alone. I am lucky to get to test out a lot of different kinds of wireless earbuds and headphones, but most of the time I use second-generation AirPods.

I ...Read more

Review: In ‘Princess Peach: Showtime!’ a Mario supporting character gets a starring role

Despite being the ruler of the Mushroom Kingdom, Princess Peach has always played a supporting role in Nintendo’s games. She’s normally the one rescued or a playable character in an ensemble adventure, but that changes this year.

For the first time since 2005’s “Super Princess Peach,” the heroine stars in her own game. “Princess ...Read more

Gadgets: Better, faster chargers

Most people want charging accessories that are better and faster. Leading accessory brand ESR helps achieve this with its new collection of Qi2 chargers.

Qi2 is the latest standard in wireless charging technology, delivering 15W of charging power and utilizing magnetic alignment for fast and efficient charging. The Qi standard was limited to ...Read more

What the ‘Fallout’ show gets right about the post-apocalyptic video game series

With superhero movies losing pop culture steam, the next big thing emerging on the horizon is video game flicks. Over the past few years, films and TV shows based on interactive entertainment have steadily gained traction, with the likes of “Sonic the Hedgehog,” “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” and “The Last of Us.”

Hollywood’s ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Wild turkey numbers are falling in some parts of the US – the main reason may be habitat loss

- Sealing homes' leaky HVAC systems is a sneaky good climate solution

- Groundbreaking discovery: Astronomers find largest black hole in Milky Way

- Fewer loon chicks surviving because of climate change, researchers say

- Surrogate otter mom at aquarium is rehabilitating pup 'better than any human ever can'