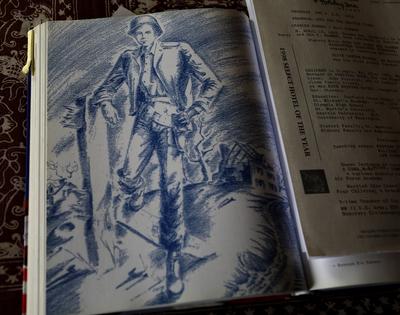

75 years ago they fought the Germans, frostbite and Hitler's desperate gamble to change the tide of World War II

Published in Senior Living Features

SEATTLE - They were, for the most part, 18, 19, or 20 years old - some just out of high school - fighting the German army in Central Europe in what many believed were the waning days of World War II.

Because of the weekslong battle they waged 75 years ago, Adolf Hitler wouldn't get the negotiated peace that he had sought from his last-ditch, surprise attack on Allied forces. The Third Reich would not live on.

Jack Van Eaton didn't know he and his fellow soldiers were making history by fighting and winning that battle that would gain its name from the bulge German forces drove into Allied lines. You don't think history while trying to avoid bombs, bullets and hypothermia.

Van Eaton, 95, of Bothell, remembers being scared nonstop.

"You don't tell your buddies. You know they're scared, too. You have artillery coming all the time. We knew that any damn second we could be dead or have a hole in our heads."

The Battle of the Bulge was fought in the middle of winter in subzero temperatures. Many suffered amputations due to frostbite. It remains the largest battle ever fought by the U.S. Army.

In the winter of 1944, the Allies were confident that victory would soon be theirs. Six months after the D-Day landings, they were rushing through France and Belgium with surprising speed.

But in the early morning hours of Dec. 16, 1944, against the advice of his generals, Hitler gambled that German troops could split the Allied armies by launching a surprise attack in the Ardennes Forest, a 75-mile stretch of dense woods and few roads that straddles portions of Belgium, Luxembourg, France and Germany.

The German army had been decimated in three years of fighting against the Soviet Red Army. "Yet, amazingly, the Germans were able to scratch together approximately 28 divisions for the upcoming offensive," says an Army history.

Facing the Germans were "four inexperienced and battle-worn American divisions stationed there for rest and seasoning," according to another Army paper. Many units were caught off-guard.

Over about five weeks, more than a million soldiers faced off - 500,000 Americans, 600,000 Germans and 55,000 British. Casualties for the two main forces were massive. For the Germans, there were more than 100,000 casualties (which includes captured and injured) with up to 12,000 listed as killed. The Americans suffered 75,000 casualties, with 19,000 killed.

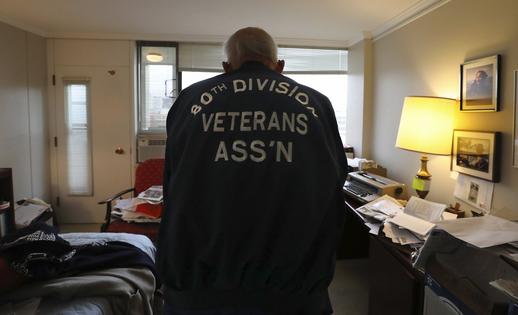

For Bob Harmon, 94, of Seattle, memories of the battle remain fresh and vivid. They can't be put aside. Harmon was drafted into the Army in July 1943, right after graduating from Olympia High School.

Harmon, a gunner in Gen. George S. Patton's forces, remembers that three times his unit tried a night crossing of the Our River from Luxembourg into Germany using flatbed boats, and all three times they were shelled by the Germans. With shells exploding around them, he remembers, the soldiers "would get nervous and start ducking and pretty soon the boat would tip over."

Soaked by the freezing waters, the battalion would turn back.

On the third attempt, Harmon, on a bazooka team with another man, managed to reach the opposing shore. "We're the only ones here," Harmon told his buddy. They ditched the bazooka in the river and let the river take them back to the Allied lines.

Later, in a letter home to his parents, Harmon wrote, "I was awake most of the night with plain outright hysteria and kept telling myself that I'd never go back."

But that night, getting ready for the fourth crossing, Harmon clearly remembers his lieutenant simply told him, "It's time to go." And Harmon went back to battle - this time his unit made it across.

Harmon, who lives at the Hearthstone retirement community near Green Lake with his wife, Gina Harmon, 88, retired from Seattle University as a history professor.

The battle reached a pivotal point at the village of Bastogne, where forces commanded by U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe were surrounded by the Germans. On Dec. 22, four German soldiers, under a white flag, gave McAuliffe a typewritten ultimatum: surrender or face "total annihilation."

The German soldiers were sent back with McAuliffe's reply: "NUTS!"

Four days later, Patton wheeled his 3rd Army a sharp 90 degrees in a counterthrust movement and entered Bastogne and relieved the defenders.

Before he died in 2016 at the age of 89, George W. Harper, of Arlington, was interviewed in 2000 for an oral history called "The Voices of World War II."

"We learned a lot of things that weren't in the books," Harper recalled about the battle. Like not hitting the ground under mortar attack.

"Because the mortars, when they hit the tree branches they blow, and the shrapnel from the mortars goes down like that. If you're flat on the ground you'd give maximum surface area to it," he said.

He laughed, "What you do is you play like you're a Green Peacer or you hug a tree as close as you can. You've got a tin pot on your head and with any luck any of the shrapnel will come down on the tin pot."

Harper told about the battle conditions for the young soldiers.

"I learned to sleep standing up next to a tree. I would start to sleep and I would sleep for 30-40 seconds and I'd start to fall, I'd wake up and start shooting again," he said.

To keep awake, "What we'd do is take the powdered coffee, pour it down like that in our mouths and grab a handful of snow to get it down to get the caffeine in us, and then we'd smoke one cigarette after another ... it was just a complete nightmare."

Harper's war ended when he was wounded in the battle.

Harper's family told a Seattle Times reporter recently that he went on to have an eclectic career. He worked as an air traffic controller, and for a time ran a telescope observatory near Mount Rainier. He also was a published writer of science fiction and nonfiction.

In Bothell, Van Eaton recalls he was 19 when he joined the Army after graduating from Yakima High School in 1942.

For a long time, Van Eaton wouldn't talk about his war experiences.

"It was such a damn miserable thing to be in, shooting at people, and getting shot. Who the hell wants to talk about that?" he says.

In recent years, though, he's talked about the war to high-school kids in the Seattle area.

Van Eaton tells them about still having the copper jacket of the armor-piercing bullet that first went into a tree, then went downward into his boot, going between the bone and tendon on his right ankle. He was hauled to a field hospital in a sled hitched to a team of horses. That earned him one of two Purple Hearts.

He tells them about the cold in what was supposedly was one of the harshest winters in decades. Van Eaton managed to get stockings from farm houses and some safety pins. He would wear one pair, and when it got wet, dry it out on the back of his uniform, and put on a dry pair.

"Having been born and raised in 50-degree below weather growing up on a Saskatchewan farm, I knew that if your feet get wet, before you know it, they're frozen," he says.

Van Eaton had a career as a Los Angeles firefighter for three decades, and, after moving here, as a Snohomish County fire-district commissioner.

When the battle was over, Winston Churchill said about the young men who fought off the Germans, "This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever-famous American victory."

Visit The Seattle Times at www.seattletimes.com

Comments