White landowners in Hawaii imported Russian workers in the early 1900s, to dilute the labor power of Asians in the islands

Published in News & Features

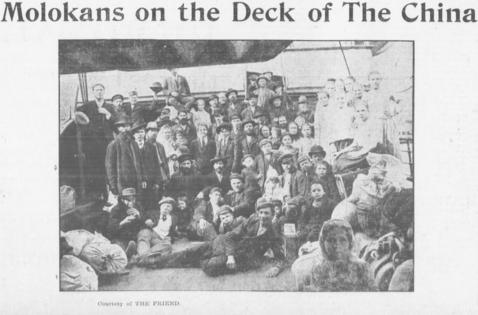

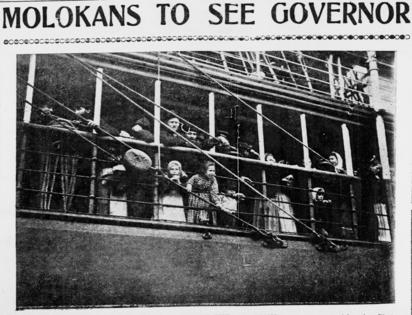

On Feb. 19, 1906, the mail steamer China pulled into the harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii. It had made the voyage from San Pedro, California, many times before, but this trip made front-page news. Local newspapers heralded the arrival of “one hundred and ten white men, women and children, the vanguard of what promises to be an influx of settlers for the Hawaiian Islands.”

A reporter from the Hawaiian Gazette recorded that they “looked to be a healthy, moral, God-fearing people.” By contrast, in 1856, some of the first Chinese contract laborers to work in Hawaii had been described as a “turbulent, stubborn, reckless class” in need of “influences tending to their improvement and conversion to Christianity” so that there might be “a blessing in store for the Chinese in the Sandwich islands,” a former name for Hawaii.

These white Christians were originally from central southern Russia and were part of a decadelong effort by the wealthy white men who owned Hawaii’s sugar plantations to find laborers who would work hard for little money. But as I have learned during my research into Russian migration to the U.S. in the early 20th century, their racial background was key to their arrival in Hawaii: They were white immigrants whom the supporters could liken to American Colonial-era settlers and those expanding west across the Great Plains.

Since the 1830s, white planters had run massive sugar plantations on the Hawaiian Islands. At first they employed Native Hawaiians. However, the demand for labor grew fast, and as some of the Native population died from European-introduced diseases, there were not enough workers for the industry. In addition, Hawaiians began to organize against meager pay and harsh working conditions as early as 1841. Faced with a possibility of large-scale unrest, the planters started to recruit contract laborers from Asia in the thousands, especially from China.

White elites, like those who overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, wanted Hawaii to eventually become a state. But opponents, like Humphrey Desmond, editor of the Catholic Citizen newspaper, feared that the Asians living there would become U.S. citizens and “dilute the citizenship” of the rest of the white-dominated U.S.

Since the 1880s, Hawaiian elites had tried bringing in workers from Portugal and Norway. They received much higher wages than the Asian laborers and were promoted to skilled occupations faster. A few white farmers also made it on their own to Hawaii, but most of them quickly gave up, their efforts defeated by the harsh tropical climate.

In 1898, the U.S. agreed to annex Hawaii, whose population was just over one-fifth European or American in ethnic background. But that meant the plantations could no longer import Asian workers. They were banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which now applied to Hawaii as a U.S. territory.

In addition, the planters now came under pressure from the growing power of the Asian workers already in the islands. In 1904 and 1905, Japanese laborers led strikes on several plantations across Hawaii, in some cases winning increased pay and other concessions such as firing of negligent overseers.

Enter the Russians.

The new arrivals to Hawaii were known as Molokans. A Christian group that had emerged in the 18th century in central southern Russia, they rejected the teachings of the Orthodox Church, which was closely tied to the Russian government.

...continued

Comments