Women in Antarctica face assault and harassment – and a legacy of exclusion and mistreatment

Published in News & Features

A federal report that, in the words of its key finding, “sexual assault, sexual harassment, and stalking are problems in the U.S. Antarctic Program community” – and that efforts “dedicated to prevention [are] nearly absent” – drew attention around the world. But as a historian of Antarctic science, I did not find it surprising at all.

The report, released in August 2022 by the National Science Foundation, which runs the United States Antarctic Program, found that many scientists and workers believe human resources staff “are dismissing, minimizing, shaming, and blaming victims who report sexual harassment and sexual assault.” A report with similar findings about its national program was released by the Australian Antarctic Division in late September 2022.

The fields of Antarctic science and exploration have long excluded women from the region altogether and still have a strong culture focused on masculinity and chauvinism.

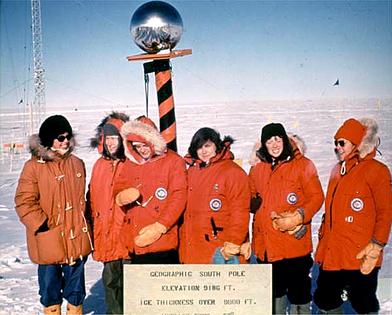

The first Antarctic expedition to include women was the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition, in 1947-1948, a U.S.-based expedition with funding from the government and private sources, led by U.S. Navy Capt. Finn Ronne. His wife Edith “Jackie” Ronne accompanied her husband, as did Jennie Darlington, the wife of one of the pilots, Harry Darlington.

Their inclusion was groundbreaking. But their presence also was perceived by many in the polar community to contribute to tensions between the young and inexperienced men, “hardening into a mold of accusation, innuendo, and dissension. … Tension and turmoil were to take precedent over pioneering,” as one historian wrote.

Jackie Ronne would return to Antarctica several times. But at that first expedition’s conclusion, Jennie Darlington asserted that “women do not belong in the Antarctic” because of the harsh conditions, which might cause a person to require assistance or even rescue. She wrote, “Men should not be put in the position of endangering his own safety for another, lesser physical human.”

Darlington also reflected on the emotional burden she undertook. Many men, including her husband, believed that “Antarctica symbolized a haven, a place of high ideals and that inner peace men find only in an all-male atmosphere in primitive surroundings.” She wrote, “My job was to be as inconspicuous within the group as possible. I felt that all feminine instincts should be sublimated. … I was determined not to act like a woman in a man’s world.”

She also commented on the psychological difficulty for both the women: “It was a tenuous balance, in which as women, we bore the major responsibility for the men’s conduct toward us. … Any drawing of attention to myself, any gesture or indication that I expected certain courtesies, any show of bossiness or pretense would have been resented.”

The global scientific effort called the International Geophysical Year in 1957-1958 changed the nature of Antarctic research from relatively small, short-term expeditions to the establishment of permanent bases on the continent. But as various countries shaped their respective Antarctic programs, many were adamant that women would not be included.

U.S. Navy Adm. George Dufek, the supervisor of U.S. programs in Antarctica, declared in 1957 that “women will not be allowed in the Antarctic until we can provide one woman for every man,” implying that there would be no need for women in Antarctica except as sexual partners for the men.

...continued

Comments